Disturbed Ecologies

No-Future Farmers

Petralia Soprana, Sicily

12. March 2019 – 20. April 2020

With Mikhail Lylov

1.

A year ago we moved to an abandoned farmhouse in the Sicilian mountains. After years of reading, writing and talking about the fabulous things animals, plants and matter are capable of, we felt they were demanding a response from us, an intervention that our artistic practice and theoretical attempts weren’t capable to submit. Furthermore, we had become sincerely worried about the species extinction rates and climate change prospects. By caring for an old fruit orchard, we hoped to join animals and plants in their struggle to survive and make our understanding of climate change less abstract and distant. We hoped the orchard would teach us an inhuman interspecies mode of care and attention that could enable us to confront the limits of the very concept of the human. We aimed for mutual deterritorializations and imagined rediscovering images, habits and activities that we might not fully understand but make us sense more explicitly our co-existence with the multispecies commons.

To comprehend climate change affectively, we had to leave our domesticated city lives.

Climate change confronts us with a strange temporality – most of the impacts will play out in the future, but the time to act is now. Climate demands an abstraction for a future that doesn’t belong to us and beings we never will encounter.

We often found the imaginaries that conjure up and dramatize climate change and the Anthropocene to be extremely limited, either refurbishing aerial apocalyptic scenarios or an enchanted, unified vision. Both fictions reinforce cognitive bourgeois values by either presuming the human has lost herself completely and needs to reconnect with the local natural environment, or by suggesting a technological totality and continuity. Many of these representations enshrine the Anthropocene as something inevitable, though bad for “the human” because “the planet” can’t be use as a resource any longer, neither emotionally nor extractively. We felt that art dealing with the Anthropocene often too-confidently replaces the natural world with the artificial, like rain with confetti or the sea with clear blue resin. For sure, the artificial and the natural can be exchanged, but what we get is different. We become different from the world. In the words of Donna Haraway, “[t]o be human is to be on the opposite side of the Great Divide from all the others […] the institutionalized, long dominant Western fantasy that all that is fully human is fallen from Eden, separated from the mother, in the domain of the artificial, deracinated, alienated, and therefore free” (Donna Haraway, 2008).

We search for unnatural nuptial encounters where one becomes an organ for the other—but we don’t want to become different, supplant what is already doing well, nor gaze from above. We want to comprehend things sideways, to be on the level of soil and plants, learning what they are made of. As an ecology of practice, we imagine farming as a way of acting alongside the eternity of the nonhuman, a diagonal movement running diffractively through the division (of labor) between the human and nonhuman. We imagine farming as being an active participation in the ongoing mutations of soil, plants, animals and climate, a participation charged with dependence. Dependence on exhausted soil and unpredictable weather.

We know things are complicated and that living in the countryside doesn’t equal sustainability and wilderness. Being in the countryside rather means to be in a less privileged space, a space where it is possible to touch the ecological destruction and the precarity of other species that in a city are often hidden from sight. We look at bare hills and learn that modern man finished the deforestation that the ancient man had begun with a clear-cut. We see how farm animals have replaced wildlife even in natural parks. We grasp how the loss of traditional crops is connected to the promise of easy farming. We witness how waste is deposited in the environment as if it were a “human right.” We feel the vibrant agency of matter when we stumble into overgrown ironing boards and abandoned TV sets. We endure tornados that wipe trees and streets away. We experience how the “cleaning” of re-wildered landscapes from unwanted vegetation with fire is a popular male sport executed with brutal commitment in the summer months. Waste, weather, erosion and fire – these keep us entangled with the landscape. We endure and we mutually become.

Of course, in the countryside we breathe fresher air and drink cleaner water than in the city. We look at bluer skies and our moods are not modulated by anti-depressants since we aren’t obligated to perform as competitive subjectivities in over-managed universities or branding galleries. On the other hand, we feel how easily manual labor wears out our bodies and a big part of our human social life depends on satellites, and if they are down, we are down as well.

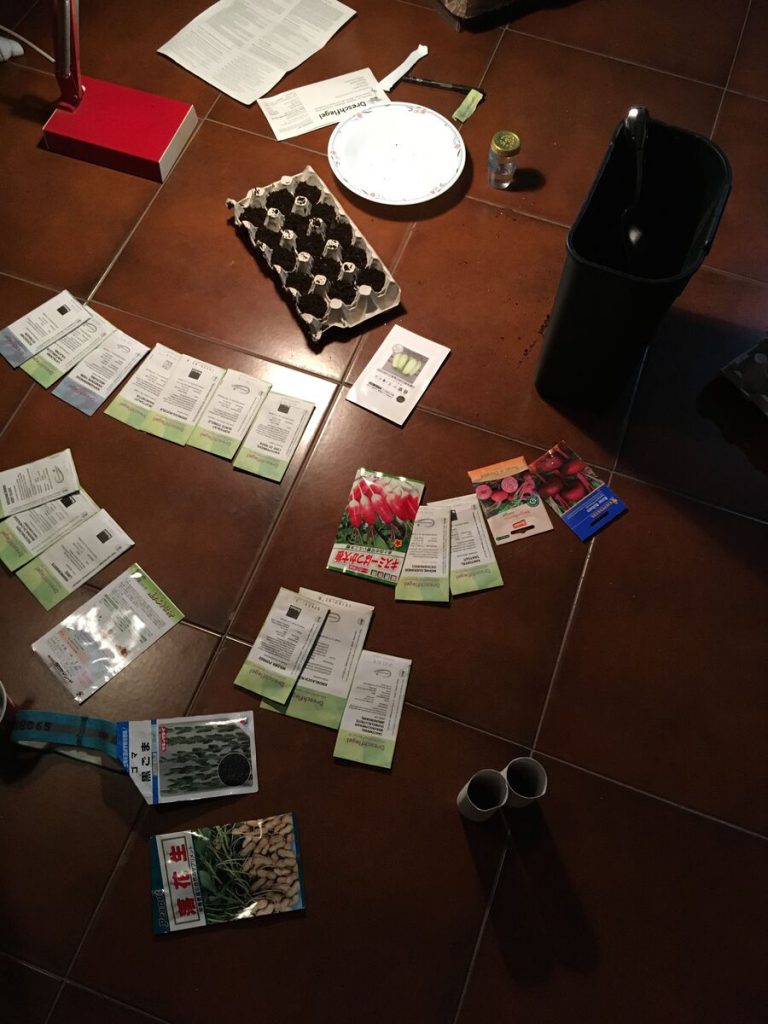

After some parts of the orchard burned away to ashes, we had to develop a new sensitivity towards our surroundings. We had thought of everything as negotiable, even the most critical situations, but the orchard taught us differently. Facing the forces of fire and closely observing the death of plants and animals around us altered our imaginary. We caught a glimpse of what a nonnegotiable defeat entails and feels like. We learned to change our habit from farming to foraging. Forests, and fields became our new garden. We dispersed, became “nomadic,” collected mushrooms, chestnuts, rosehip, herbs, diverse berries, plenty of vegetables and firewood. After a while we resettled again, planted new trees and reestablished the vegetable garden by following Masanobu Fukuoka’s understandings and practices, which means trying to farm in the most inhuman manner possible. Fukuoka’s Natural Farming practice follows the principle of “not doing.” Restricting oneself from activity and closely observing the spontaneity and creativity of nature is, of course, influenced by a Zen Buddhist practice. Instead of cultivating nature, like biodynamic agriculture, permaculture and traditional farming practices, Natural Farming limits human interventions and instead copies natural processes. It explores the sensitive and communicative dimensions of plants, soils and their companions. Therefore, it prohibits tilling, the additional use of compost or fertilizer and any other processing of the soil. The vegetable garden is made in a traditional Japanese raised-bed style. We use a spade with a straight edge, cover the soil with grass and burry kitchen scraps. We add water and plant additional seeds or seedlings, so we don’t get angry at the slugs. In the other parts of the orchard we cut grass to prevent fire and scatter vegetable seeds in a semi-wild manner. In the end we take the fruits and leave the rest to the field.

2.

I began writing this in the beginning of a pandemic, which has thrown us into the present. All around us Corona destroys and takes many lives; it has turned everything upside down. We act accordingly – we freeze, we stop. It is possible to halt the train of progress. In viral times we mobilize our capacity to completely change our habits. We take the burden that comes with the gift of vulnerability. We realize the gravity that comes with interconnectivity. But viruses are neither aliens nor enemies. They have always lived within us. They force us to form rhizomes with bats, pangolins, birds, ticks, foxes, monkeys, cows and camels. They demonstrate that we are intrinsically linked with more-than-human beings and that we are vulnerable. They re-program our genetic codes with their molecular intelligence and teach us genetic engineering. They out-perform the holy grail of our immune system only to prove that immunity does not exist. For the microbiologist Lynn Margulis, all genetic information and its variations are the result of the interactions and transfers provided by bacteria and viruses. Microbial populations push evolution, or rather involution in Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s terms, by propagating new alliances between very different organisms.

For about four decades many of those microbial populations, which might have been only slowly growing or even sleeping eternally in some host, have been propelled to populate the planet as new infectious diseases. We have been busy learning their names—Ebola, SARS, MERS, Lassa, HIV. In the present moment, we listen attentively to virologists and count numbers, compare data and statistics, all with unprecedented sincerity. But what of the warnings issued by climate science? Aren’t the pandemic and the planetary health effectively interconnected? Are they not outcomes of the same patterns of development only performed on different time scales?

Humans have put an immense pressure on the lives and habitats of plants and animals. Our mobility and infrastructure have turned an epidemic into a pandemic. We intrude, trade, consume, exhaust, infect, eliminate or enslave almost all life on the planet. In so doing, we have crossed a line in the earth system that marked stability for the health of humans and other species, and we know it. We have gained experience and gathered knowledge. We have analyzed the details of the ecological disaster we have imposed upon the earth. We know our relationship to the mechanisms that provoke such massive fires, terrifying floods and hurricanes, melting glaciers and permafrost, impoverished environments and identities. We know that we are the crisis, and that our activities have brought us to a state of perpetual emergency and mass extinction. We violated the health of the earth and initiated a process that extends beyond our capacities – yet why don’t we panic? Indeed, it seems this knowledge has only an immaterial or abstract quality. We don’t change our habits, our diets, the way we live, our mode of production and consumption. We don’t interrupt, stay home, become inhuman or inactive for the survival of other species, nor even our own. Instead, we hold onto our fatal aspirations—our sense of exceptionalism and our libidinal investments tidily in place. We take increased risks in the way we live, eat, travel and trade. In so doing, we make common cause with denialist, risk-taking politicians. The current denial of the coronavirus’s effects by rightwing politicians illustrates our own arrogance and ignorance toward the wellbeing of the planet as well as human and other-than-human lives. The dark side of our affluent, globally connected, desk-work societies, with their utilitarian alignment, has become visible in the treatment of migrant harvesters who have been exceptionally airlifted into Western European countries. Because none of their citizens care to leave the comfort of their home-offices to do environmentally destructive agricultural work in hazardous conditions for almost no wage, yet still want their supermarkets stocked with cheap produce, governments have made every effort to ensure the exploitation of impoverished labor markets in the East. At the same time, we consume and accelerate digital industries. We nonchalantly zoom in to conferences, seminars and archives, while we shop, demonstrate and chat online, as though digital media weren’t based on raw matter nor entangled with environmental violence.

Right now, during the pandemic, we are propelled into the present and we are able to touch the contradictions, class divisions and xenophobia that manifest our lives. By this we gain an understanding of what is crucial for our maintenance, and what we can abandon. Though we can’t return to a before climate change, we need to find a relation to the world that can afford us. Can we collectively respond to and mobilize around the current moment as a turning point? Why not save more lives and say goodbye to the globalized economy as it was until the end of December 2019? It turns out most flights are not essential, as are major entertainment events. It seems we can live without avocados and internet-connected coffeemakers. Sublime state interventions are welcomed. Reduced working time, a global health system and a living wage for all seem possible in order to provide a vital and productive sustainability.

3.

In a time of new infectious diseases, being in the countryside is just dandy. Our lungs don’t have to struggle against the double burden of air pollution and infection. We can fall in love again with social distancing. We don’t need to worry that the food eat and the things we use are carrying contagion. We can keep touch.

In viral times, good things come out because we observe the immediate effects of our direct in/actions.

4.

And now as a poem:

How

To

Become

Always

Been

Post-Anthropocene